During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the African-American community faced significant challenges, including segregation, disenfranchisement, and racial violence. It was a time when white philanthropy and the broader American society grappled with the question of what to do with the newly emancipated Black population. Amidst this, prominent Black leaders like Booker T. Washington and Bishop Henry McNeal Turner emerged, offering different approaches to uplift their people.

Booker T. Washington and the Atlanta Compromise

Booker T. Washington became one of the most influential African-American leaders of his time, particularly due to his Atlanta Compromise speech in 1895. This speech was delivered at the Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition, a significant event that symbolized the industrial and agricultural progress of the South. Washington’s speech is often viewed as a pivotal moment in American history, where he outlined his philosophy for the upliftment of Black Americans.

In his speech, Washington advocated for vocational and industrial education, economic self-reliance, and a gradual approach to gaining civil rights. He urged Black Americans to focus on building their economic base rather than demanding immediate social equality. He famously advised the Black community to “cast down your buckets where you are,” emphasizing that they should seize the opportunities available in the South rather than seeking equality in the North or through political means. This message resonated with many, particularly those in the South who lived under the constant threat of violence and economic hardship.

The Dual Nature of Washington's Leadership

Washington’s leadership was multifaceted and often viewed as contradictory. On the one hand, he secured substantial funding from white philanthropists, which helped him build the Tuskegee Institute into a highly respected institution. His emphasis on hard work, education, and self-help earned him admiration from many Black Americans, especially those who saw his approach as pragmatic given the harsh realities of the time.

However, Washington’s stance also attracted significant criticism. Many African-Americans, including notable figures like W.E.B. Du Bois, viewed his approach as overly submissive and accommodating to the oppressive system. Du Bois and others believed that Washington’s strategy of economic progress at the expense of immediate civil rights delayed the struggle for true equality. They argued for a more confrontational approach, demanding political and civil rights as essential elements for genuine progress.

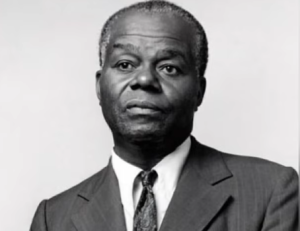

Dr. John Henrik Clarke’s Critique of Booker T. Washington

Dr. John Henrik Clarke, a prominent historian and scholar, offered a critical analysis of Washington’s leadership, particularly his Atlanta Compromise speech. Clarke argued that Washington was, in many ways, a leader chosen and elevated by white America to serve their interests. According to Clarke, Washington’s speech was a masterful piece of oratory designed to appeal to both Northern and Southern whites, as well as the Black community. He described the speech as a “con game,” where Washington cleverly played to the different audiences, promising things he could not deliver.

Clarke pointed out that while Washington’s speech appealed to the emotions and economic interests of the South, it did not address the deeper issues of racial injustice and inequality. Washington's suggestion that Black people should focus on farming and vocational work rather than politics was seen as a way to keep them out of the political sphere, thus pleasing Southern whites who feared Black political power. Furthermore, Clarke noted that Washington’s message of economic self-reliance without the demand for social equality was a significant compromise that many in the Black community could not accept.

The Aftermath and Legacy of the Atlanta Compromise

The immediate aftermath of Washington’s speech saw a mixed response within the Black community. Some viewed it as a practical solution to the problems they faced, while others saw it as a betrayal. Clarke highlighted that many Black people began to “vote with their feet,” leaving the South in search of better opportunities elsewhere, signaling their dissatisfaction with Washington’s accommodationist approach.

Washington’s impact on the trajectory of African-American progress is undeniable. His leadership and the institutions he built provided a foundation for the education and economic advancement of many Black Americans. However, his strategies also sparked a debate that continues to this day about the best way to achieve racial equality. The tension between economic progress and the demand for civil rights, as embodied in the differing approaches of Washington and Du Bois, remains a central theme in the ongoing struggle for justice and equality in America.

In conclusion

Dr. Clarke’s critique of Booker T. Washington highlights the complexities of leadership in a racially divided society. Washington's Atlanta Compromise was both a significant achievement and a source of controversy, reflecting the difficult choices Black leaders had to make in navigating a hostile environment. His legacy, as seen through the lens of Clarke’s analysis, invites ongoing reflection on the strategies employed by African-Americans in their pursuit of equality and empowerment.